Ch. 4: Guet N’Dar

It was already too hot. Moving south across N’Dar Island, Lomax stopped, removed his cell phone from a pocket of his photographer’s vest, and checked the temperature: 29°C. I stopped next to him and asked, “Any rain in the forecast?”

“No,” Lomax replied, studying the information on the screen of his iPhone. Laughter erupted, and we turned our heads to see François standing behind us while about 10 feet to his right, hopping across the west side of the dusty street, a large, black raven was picking at remnants of fruit and fish.

“Rain?” François said, a smile forming on his face underneath the baseball cap he wore. “In the middle of May?” He looked from me to Lomax. “You serious?” The big black bird grabbed the fish head off of the asphalt a short distance away, alighting on the roof of one of the bars near the corner of Rue Blaise Diagne and Rue Blanchot. François’ smile disguised his skepticism. “The bird is a scavenger,” François noted, “and flies on the winds along the coast. But it’s hard for him to land and take off again in a narrow street due to his size. He’s taking a risk.” Lomax and I remained silent. The raven cawed from its perch on the roof, almost dropping the fish. François didn’t know what to make of Lomax and showed some caution. “You know we’re in the dry season, right?” François asked. He glanced up at the big black bird which now looked back and shifted the fish to a large claw.

I recalled that St. Louis received about 10 inches of rain fall each year with most of it falling during the months of August and September with a smaller but measurable amount falling during July.

“So you didn’t bring a rain coat?” Lomax responded, putting his cell phone back in his pocket. “Or your poncho?” Lomax added, zipping up the compartment into which he had placed his iPhone. The raven unfolded its wings, took to the air above the top of the building, and rose into the sky. “You can’t be too prepared,” Lomax said, not cracking a smile, although I knew he was having fun at François’ expense.

I adjusted the wide-brim hat on my head and watched the black shape of the bird become smaller in the sky as it rose higher before shifting my gaze farther into the distance beyond the buildings along Rue Blaise Diagne and toward the West. We were half a mile from the Atlantic Ocean although it was out of sight on the other side of the settlements on the spit of land known as La Langue de Barbarie. An entire mini-city had taken shape there, a place we wanted to explore.

It was going to be a difficult and uncomfortable task.

Relief from the heat, I realized, could come from a breeze which could start blowing off the ocean, but it wasn’t guaranteed. I glanced at the digital watch on my wrist: 1:04. We had 26 minutes to reach Ismael at the rendezvous point, but I knew he would be there even if we arrived late.

In practical terms, Ismael had no choice but to wait for us and for our next requests for his help. I looked at Lomax. Under the photographer’s vest, he wore a light blue, short-sleeved polo shirt. Over the vest, he had on a backpack in which he carried several camera lenses. The Pentax camera itself hung by a strap from his shoulder. He carried too much equipment, but I knew he would argue it was necessary and he would vouch for his results. Lomax stopped in front of an orange storefront, moved the camera up to his face, and took several photos before previewing the images in the small LCD at the back of the camera. I could tell he was happy not only with his photos but also with his subjects. The people in the narrow streets were unusually photogenic. I admired their clothes and personalities. I shifted my gaze to Madeline, who had stopped next to me and taken off a pink cotton sweatshirt.

Eastern Shore, N’Dar Island, St. Louis

“I think we made a mistake in deciding to come with you this afternoon,” Madeline said, glancing at Sylvie, who walked slightly ahead of her. “It was cooler yesterday afternoon,” Madeline added, “when the clouds came in after lunch. We should have taken our tour of Guet N’Dar then.”

“Yes, but today it seemed it was going to rain a little and cut down the heat,” I replied, looking around for François. “Anyway, I couldn’t go yesterday afternoon,” I explained. “I had to talk with one of my colleagues in Washington, D.C.”

“About what?” Madeline asked. “Are you busy at work? Are you keeping a journal or writing an article?” She peered into my face. “You were a journalist at one point. What are you now?”

I looked at Madeline. She was Parisian and took pride in her English but also enjoyed asking questions. François caught my attention. He stopped on the other side of Madeline and appeared to be listening. “I have a new project,” I replied finally, starting to walk again while shifting my gaze back to Madeline. She arched her eyebrows. “It’s an analysis of the U.S. government’s decision to take troops out of the Sahel,” I said.

Madeline and François also started to walk again.

“Really, why—” Madeline began.

“It was my idea to postpone our tour too,” François interrupted.

Madeline glanced at François, surprised. “I couldn’t go yesterday afternoon either,” he added. “I had to go across the river into the main part of St. Louis to meet an old Senegalese colleague.” François paused. “He was a college teacher for many years,” François continued. “Now he’s retired.”

A silver-colored Olympus camera hung from a strap around François’ neck, but it was much smaller than the medium-format model that Lomax used. François brought the camera up to his face, changed his mind, and allowed the camera to dangle from his neck again. He removed a handkerchief from the back pocket of his expedition-style shorts with one hand, lifted the baseball cap off his head with his other hand, and used the handkerchief to mop the sweat from his bald head.

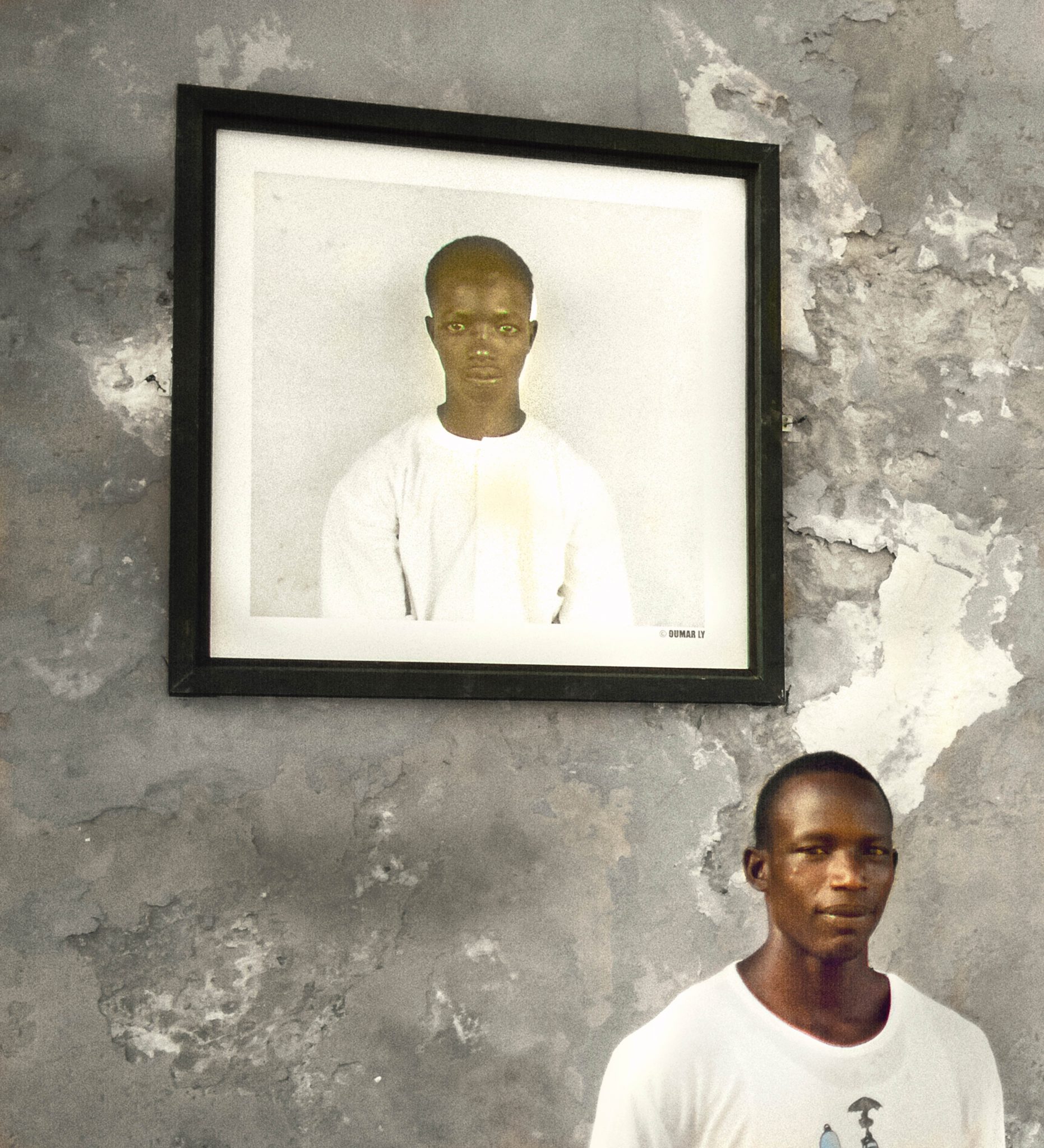

Young Man with Portrait of His Grandfather

“Sure, we’re on the edge of the Sahara Desert,” François continued, replacing the now soiled handkerchief in his back pocket while placing the baseball cap back on his head again, “but St. Louis gets much less rain fall now than before.” François gestured with his right hand. “I’ve been coming here for 25 years,” he continued. “Nobody can deny the impact of climate change.” He looked at Madeline, then at me. “What does the future hold for these people?”

At that moment, I had nothing to say in response to François. Instead I focused on the dusty street ahead, where Lomax now stood next to Sylvie on a corner, waiting for Madeline, François, and me.

We turned right on Rue Blanchot as a group of men in traditional dress approached. Leading the way was a particularly old man who wore a white skull cap on his head as well as a flowing white robe extending from the bottom of his neck to his feet. I could see the ends of a pair of white pants just above his leather sandals. Behind him three other old men also wore flowing white robes; however, these men, in contrast to their leader, were bare headed. No one else walked along the sunlit street. Occasionally starlings flitted among the buildings on either side of the street, sometimes darting down to the dusty asphalt to peck at one object or another before alighting on rooftops.

The white-robed old men smiled and greeted us in Wolof as they passed. I wondered if they would walk far in the heat. I watched as Lomax stopped and took a photo of the ancient men. Sylvie approached Madeline, who stood next to me. On the right side of Rue Blanchot, I recognized the Banque Internationale Pour le Commerce where Lomax and I had found an ATM two days previously. The bank was closed for business, and the street in front of it deserted. Madeline put her arm around Sylvie’s shoulders.”

“Tonight we have an appointment with Ismael and his partners,” Madeline said to me. “They’re bringing some gold pieces.” Madeline paused. “The gold comes from their mine, I believe.”

Sylvie smiled. Madeline laughed loudly. I thought I detected a note of anxiety in Sylvie’s muted response. The idea of going on a shopping spree for gold in Senegal seemed quite odd to me.

“My mother in Combs-la-Ville is counting on me,” Sylvie said.

Looking toward the Atlantic Ocean

Riverfront

Green and blue with flashes of golden light, the water appeared before us as we approached the end of Rue Blanchot and turned left on an equally narrow street, Quai Giraud, alongside the river. Figures dotted the river bank, busying themselves with unloading the big wooden boats along the water’s edge. While men removed plastic containers colored blue, red, and yellow from the boats and placed the containers on the sand, women bent over plastic tubs in which they washed fish with water they transferred from other plastic tubs.

Lomax was taking photos rapidly. François leaned over the wall along Quai Giraud and began pointing his camera down at the boats and fishermen. Two large men on the river bank looked up, paused in their work, and waved at Lomax and François. One young woman glanced in our direction, but she didn’t stop what she was doing.

Walking next to Madeline and Sylvie south on Quai Giraud, I pointed to a bridge 300 feet ahead of us, connecting the western edge of N’Dar Island to the eastern edge of La Langue de Barbarie.

“The bridge is named Pont Moustapha Malick Gaye,” I said. “We’ll meet Ismael in the middle of it.”

Madeline looked at me. “I’m so glad you’re here to lead us,” she said. “I don’t think we could find our way without you.” She touched me lightly on the arm. “In fact, Sylvie and I were on that bridge yesterday. We found it for ourselves, although we didn’t go all the way across and set foot on La Langue de Barbarie.”

Madeline, Sylvie, and I halted at the bridge’s entrance, waiting for Lomax and François who were looking at an image on Lomax’ camera.

“Oh, I want an ice cream,” Sylvie said, spotting an ice cream shop on the street behind us. I could just make out the words, Happy Gelato, above the front door of the shop. As Sylvie started walking toward Happy Gelato, Lomax arrived.

“I’ll go with you,” Lomax said to Sylvie. François approached and stood next to Madeline and me.

“Lomax got some good shots,” François announced.

“So tell me about your life in Washington, D.C.,” Madeline said, turning to me. “Do you have a girlfriend?”

“Sure,” I replied. I didn’t say anything more.

Madeline looked at me.

“Well?” she said finally.

François stared down at his camera, which he held in both hands.

“Well what?” I replied.

François moved to one side, embarrassed by Madeline’s questions.

“Aren’t you going to tell me anything more about yourself?” Madeline continued. I looked back at her.

“Tell you what?”

“Your girlfriend’s name?” Madeline said. “And what she does?” Madeline continued looking at me. “And if you have been with her for long.”

I didn’t reply.

A few minutes later, Sylvie re-appeared, holding a paper cup with vanilla ice cream in one hand. Lomax followed and stopped next to Sylvie, holding another cup with strawberry ice cream overflowing its edges.

“This stuff is good. I should have gotten a bigger container,” Lomax said, using a tiny spoon to shovel ice cream into his mouth. “Isn’t it time to meet Ismael?”

Madeline glanced at me before turning toward the bridge. “Actually,” she replied to Lomax, “you could have brought me a cup. You’re not a gentleman.” Then she started walking across the bridge. “Let’s go,” she said.

“You’re right,” Lomax replied, laughing. “I’m not.”

People on the River Bank

Pont Moustapha Malick Gaye

I had the impression Ismael had been waiting for us for some time. When I saw him in the middle of Pont Moustapha, I checked my watch. We were not late; we were early. Ismael, obviously, was anxious. He leaned against the concrete railing and stared down into the waters of the Senegal River, and the thought occurred to me that our guide was wholly dependent on us. Madeline and Sylvie, who were about 15 feet ahead of me, moved toward Ismael, talking in French to each other. Probably, Ismael was excited by Sylvie’s interest in gold, thinking he could trick her.

To my left, Lomax ate his ice cream as he walked, moving westward on the bridge. His large camera, now idle, dangled on its strap from one shoulder. Although Lomax periodically looked up, he didn’t seem to care now about views either to the north or to the south of the bridge. To my right, François stared into the distance as he walked. He, too, didn’t take photos. I stopped and removed a water bottle from my backpack, unscrewed its top, and drank the cold liquid while the sun beat down. As I tilted my head back and poured the water down my throat, I saw a mass of white clouds building in the sky over the Atlantic and wondered where the clouds came from and why they had formed in an otherwise blue metallic void. But maybe rain was falling somewhere out there.

When Ismael saw us, he stood up, but seemed uncertain as if he didn’t know why we had appeared. His reaction was strange. Under the bridge the green water appeared to flow slowly, almost gently, and then, after a moment, a long wooden boat with two men standing at the stern passed under the bridge. Ismael directed his gaze toward Sylvie.

“My partners and I will meet you in the bar at the Siki Hotel at 7:00 this evening,” Ismael said in French. “We’ll have the gold pieces with us. But my partners only will accept bills in euros.”

Sylvie seemed displeased, but she smiled and carefully placed her empty paper cup in a cloth bag hanging from her shoulder. Lomax placed his own empty cup into her outstretched hand. I recalled comments Sylvie had made earlier in the day, when she indicated she was upset by the mounds of trash lining the roads in St. Louis and by the constant reminders of the hopelessness of Africans. From previous conversations, I knew Sylvie had grown up in Cameroon. Also, I assumed that, as an anesthesiologist in a major hospital in Paris, she was used to high standards of hygiene.

Lomax raised up his camera and took a photo of the group. Ismael seemed uncomfortable. Watching Lomax, François raised up his own camera and took a second photo. Madeline stared at François. Beads of sweat dotted her upper lip.

“What’s our plan for the afternoon?” I asked Ismael.

Ismael glanced at me. “We go to the southern part of Guet N’Dar,” he replied, “and stop to talk with people on the street.” He paused. “Before we start, I go to the market and buy a large bag of different types of candy.” He paused again. “I give the candy to children along the way.” He glanced at Lomax and François. “They will like the candy, and the mothers and fathers allow you to take photographs of their families.”

As I listened to Ismael, surprised by his ingenuity, I allowed my gaze to drift toward the eastern shore of La Langue de Barbarie. To the north of the bridge, I saw a bustle of activity. As many as 100 goats were jostling on the sand next to the water. To the south of the bridge, I saw men and women unloading boats along the water’s edge, just as they had been doing on the western shore of N’Dar.

“How many people live on La Langue de Barbarie?” I asked.

“About 80,000,” Ismael replied, “a lot of people in a small area.” He swept his arm toward the river and pointed to the Atlantic Ocean not far away. “All of them depend on the sea for food.” He paused. “The number of residents used to be much greater,” he added, “but many couldn’t survive here any longer.” He glanced at me again. He looked eastward in the direction of the distant land mass where Senegal became part of the African continent. “They had to leave because their homes were destroyed by floods. There are many storms and rising seas.”

I followed Ismael’s gaze toward the eastern horizon although I couldn’t see past the buildings of the old town of St. Louis which occupied N’Dar Island. But I didn’t say anything. I didn’t have more questions. I already knew the answer to perhaps the most important matter—that everybody would have to leave soon, including many on N’Dar Island. Madeline leaned into me while looking at Ismael. She looked at the river.

“What about the river?” Madeline asked.

“What about it?” Ismael responded. “The people here use the river only to get out to the sea,” he added. “That’s where the fish are.”

“You mean sardinella?” Madeline asked, referring to the ray-finned, coastal fish which, accompanied by white rice, represented Senegal’s national dish. Sardinella was the diet for every man, woman, and child along the coast and for many miles inland too.

“Yes,” Ismael said. He had regained his confidence. “Let’s go.”

Following Ismael, we moved across the final section of the bridge and walked onto La Langue de Barbarie. As Ismael led us toward a cluster of buildings across from the bridge, he held up a cell phone. When he spoke into the phone, he spoke quickly in Wolof, and I heard him say the name of everyone in our group, except mine.

Boats along the River

Marché Top

Standing before the front door of a two-story brick building painted white with a green trim, Ismael turned and held out his hand. “I need 15,000 CFA francs for candy,” he said. I saw the words, Marché Top, painted in black on the white brick above the door. I turned toward the road running along this side of the river. The road, known as Rue NDT-01 according to the map I had consulted earlier, was crowded.

Standing before the front door of a two-story brick building painted white with a green trim, Ismael turned and held out his hand. “I need 15,000 CFA francs for candy,” he said. I saw the words, Marché Top, painted in black on the white brick above the door. I turned toward the road running along this side of the river. The road, known as Rue NDT-01 according to the map I had consulted earlier, was crowded.

“Isn’t that a lot of money for a bag of candy?” Madeline asked, polishing the lenses of her sunglasses with the edge of her shirt.

“I left my wallet in the safe at my hotel,” François declared.

Lomax was adjusting the settings on his Pentax and took a photo of a goat in the middle of the road. I removed some bills from my pocket, but, before I could hand them to Ismael, Sylvie placed her own bills in Ismael’s hand. Ismael disappeared inside the store. On the east side of Rue NDT-01, just north of the western end of the bridge, the herd of goats came closer and now occupied parts of the street. Three men herded the goats while talking with three other men who were examining the animals.

“The owners of the goats are negotiating with buyers,” François announced. “The buyers want to select the largest animals and pay the lowest prices.”

Lomax shot a series of images. François raised his camera to take photos, but four goats suddenly rushed at him and began nibbling at his shirt and his shorts. François pushed the goats away. One of the herders spoke a few words in Wolof, and the four goats ceased. A few minutes later, Ismael emerged from the store carrying a large plastic bag in one hand. All of us could see a jumble of many types of candy mixed together through the clear plastic.

Goats

“How much did it cost?” François asked in French.

“Do we need a receipt?” Madeline asked. Then she smiled.

Ismael, who found himself the object of attention, started to cross the street, and we followed him to the southern side of Rue de Pont Moustapha. Then, looking down the street farther to the West, Ismael pointed us in the direction of the intersection of Rue de Pont Moustapha and Avenue Dodds where, in the middle of the intersection, we could see a monument to World War I featuring two white-washed statues, one depicting an African soldier and the other a French solider facing toward the East.

“As soon as we reach Avenue Dodds, we’re going to turn south and enter the neighborhood of Guet N’Dar, the center of the fishing community,” Ismael announced. “The men and women of Guet N’Dar provide the fish which feed Senegal. There are more than a million people in just Dakar.” Ismael paused. “But Senegal is not the only country depending on the fishing families here.”

I knew the waters off the coast of Senegal, in combination with the waters off the coast of Mauritania to the North, were among the richest fishing grounds on the planet. They supplied the fish which in turn supplied 75% of all protein consumed by the people of Senegal and its neighbors to the West, the nations of Mali and Burkina Faso with a combined population of 60 million people. In addition, the same waters were the source of the fishmeal fed to livestock in China. Almost half of the fish caught off the coast of Mauritania were ground up for fishmeal in factories in Mauritania, and then it was sent to the Chinese mainland. Ismael pointed toward the wider, busier street up ahead.

“Avenue Dodds is the main street from north to south in Guet N’Dar,” he explained. “At southern end, it stops in an area for refrigeration trucks. They load up with fish from the day’s catch. At northern end, the street stops and then starts again in another direction. There, you find Mosquée Ghoulamou Rassoul, the largest mosque in St. Louis.”

“We walk all the way down to the truck stop on Avenue Dodds,” Ismael continued. “We stop at some places along the way. I want to show you the main mosque in southern half of La Langue de Barbarie. This trip takes us a couple of hours. We pay a horse-drawn cart to get back to the hotel.”

I had been wondering how far we were going to walk. The idea of walking for another two hours seemed out of the question.

A small wooden cart pulled by a white horse approached. Sitting in the cart were three young men. The animal moved slowly, as if it were asleep. I looked forward to sitting in the back of a similar cart and relaxing while townspeople, goats, and other animals of La Langue de Barbarie went past.

“The trucks on Avenue Dodds are loaded with fish every day, right?” I asked Ismael. I hadn’t seen any refrigerated trucks coming and going over Pont Moustapha or, for that matter, over Pont Faidherbe, which crossed from N’Dar Island to the mainland.

Lomax took a photo of the three men in the cart as the horse slowly proceeded toward Pont Moustapha. The men stared at us as if we were aliens.

In the same moment, Ismael looked at me with an expression of disbelief. It occurred to me he considered both the question and the answer unnecessary. After a few moments, he replied.

“Yes,” he said. “The trucks are sent across Senegal every day.”

As we moved west toward Avenue Dodds, we passed a long line of vendors selling their wares on the south side of Rue de Pont Moustapha. In both small stores set back from the street and make-shift displays erected in the middle of the sidewalk, men and women sold a variety of goods from belts and dresses to laundry soap and shampoo and to magazines and newspapers.

A group of men approached, moving toward us on the sidewalk on the south side of the street. Each of the five men wore the traditional attire of West Africa. The flowing, wide-sleeved robe, known as boubou in Wolof and shown off by the elderly man at the head of the group, was a dark shade of green with embroidered designs of a golden fabric. Immediately behind him were two younger men, each clad in a boubou of a light shade of blue featuring isometric shapes made of white stitches. The final pair of men, in their mid-20s, also were dressed in ornate boubous, both of a purple color with designs formed with red stitches.

Together the men presented a shocking display of style, a spectacle I had seen only one time before in a marketplace in Dakar where women adorned themselves in equally fine robes and jewelry as they moved among the rows of vegetables, shopping for food.

The men smiled at us, uttering greetings in Wolof as they passed, proceeding in the direction of the bridge.

“Wouldn’t you like to wear a boubou?” Madeline asked, grabbing my arm. I stopped in my tracks. Madeline turned toward the men disappearing down the street just before the Moustapha bridge. “I think it would be a good idea,” she continued.

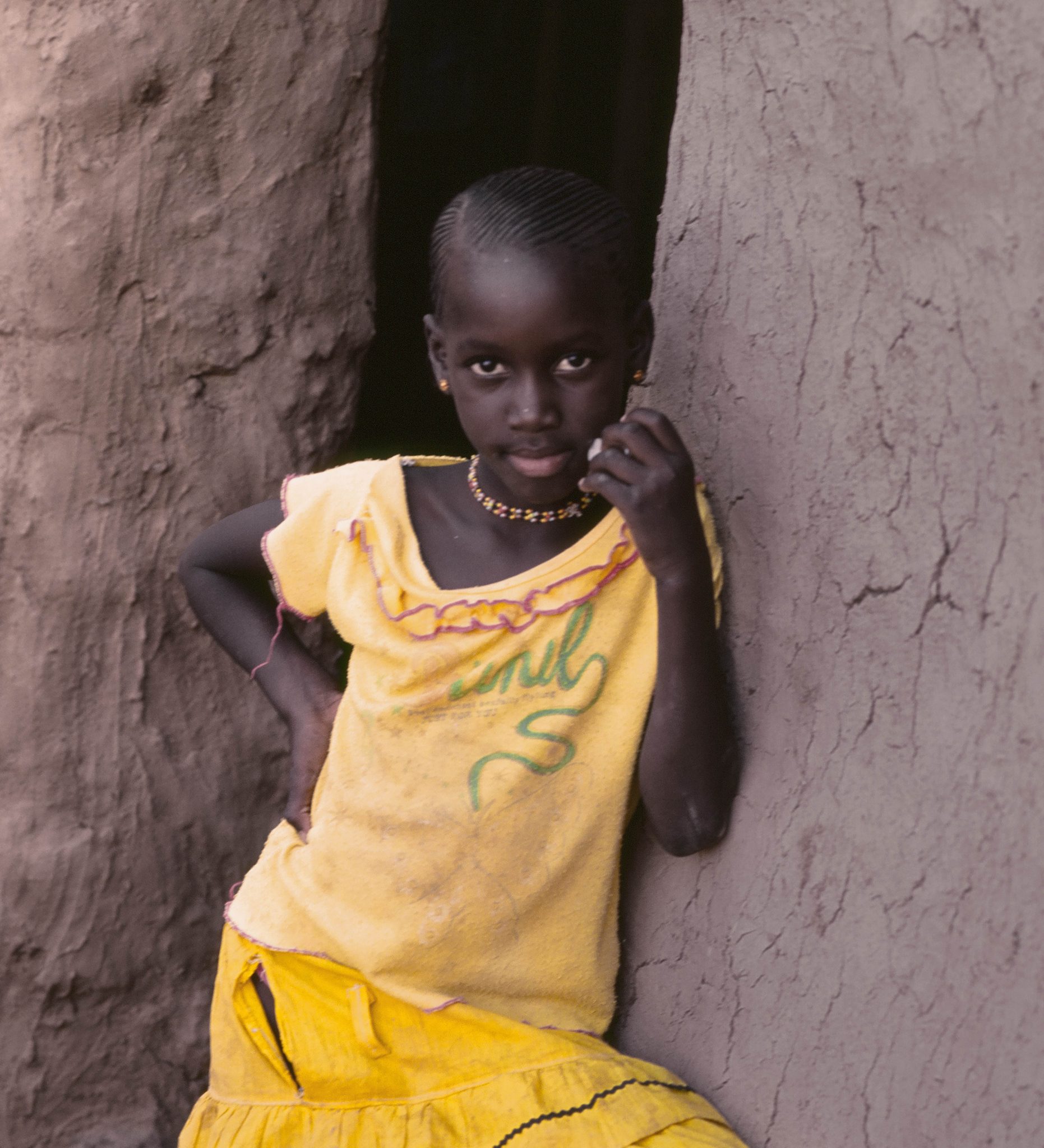

Woman with Daughter

“Maybe not,” I replied. I assumed Madeline was joking, but still I considered the idea of trying something new although I preferred the idea of modern-style clothing. I turned to François who had stopped next to Madeline. “Do you know where I can find robes like those men are wearing?” I asked.

“There are a couple of places in St. Louis,” François replied.

“Can you show me?” I said.

“I have a boubou,” François interjected. “It’s hanging in the closet inside my hotel room right now. I could have worn it today, and I should have worn it.” He looked at Madeline. “It’s black,” he added. “You’ll see when I wear it tonight. I put it on several times a week when I’m in Senegal, mainly in Thies or Dakar.”

“What’s tonight?” Madeline asked, glancing at François before looking off into the blue sky above the Atlantic Ocean. Then she looked at me and glanced back to François again before removing her sunglasses and examining their lenses for dirt. She took a small cloth from her bag and carefully wiped her lenses. Then she placed the glasses back on her face.

“I thought I would meet you and Sylvie at the bar of the Siki Hotel after you finish your business with Ismael,” François replied. “What time do you think you’ll be done with him and his partners?”

“I don’t know,” Madeline said after a few moments. She started examining the lenses of her glasses again, forgetting she had just cleaned them. It occurred to me that she was tired after walking in the heat for almost two hours and now couldn’t remember what she had planned for the evening. “You’re welcome to join us if you want,” she added. She turned to me, “You too,” she said. “It will be more fun with more people present. We can drink some of the local beer. Or have a cocktail.”

François shifted his attention.

“I’ll have to talk with Ismael,” I replied to Madeline. “I thought I was going to meet with him and a few of his contacts at 7:00 this evening at a restaurant called Flamingo.” I glanced at François, who was watching me closely. “Last night, I met Ismael and another of his contacts, a professor, at the same place.” I looked at Madeline. “But now it appears you and Sylvie will be meeting with Ismael and his partners at the Siki Hotel.” I paused again, still looking at Madeline. “Ismael can’t be in two places at the same time. He’ll have to clear up the confusion.”

Mini-City, La Langue de Barbarie

Madeline turned to Sylvie, who approached from the opposite side of the street.

“Instead of a business meeting we’ll just have a party tonight,” Madeline said in French to her friend.

“Why? What’s going on?” Sylvie replied in French.

“Everybody, let’s go,” Lomax said, approaching from the end of the block. “Ismael is waiting on the corner of Avenue Dodds.” We joined Ismael in front of the doorway of a small store where he was holding his cell phone up to his face.

“We’re turning down Avenue Dodds now,” Ismael announced, pulling his phone away from his mouth but not placing it back in his pocket. “We’ll start walking into Guet N’Dar and go down to end of Avenue Dodds.”

It seemed like Ismael thought he was still talking on his phone, describing what we were doing to someone listening on the other end of a live connection. It was clear he was trying to carry off several tasks at once and, as a result, confusing everyone.

To my left, through the doorway of the small store, I could see bags of rice which were stacked just inside the doorway to one side. But also, noticing a small banner posted above the doorframe, I deduced the store sold SIM cards and credits for mobile telephones. To my right, on the dusty street, another small wooden cart pulled by a horse was moving through the intersection with two men, both of whom wore soccer jerseys in the colors—green, yellow, and red—of the Senegalese national team.

Lomax took a photo of the horse and the two men.

In the middle of the intersection was a large pile of melons which surrounded a woman who sat under a red umbrella and waited for customers. I heard a noise to my right, looked up, and saw a raven walking across a concrete wall on the second level of a building in the first block of Avenue Dodds. Either the upper story of the building had been abandoned in one of the phases of its construction when its owners ran out of money or it had been destroyed by a powerful storm off the Atlantic. I had read that all of La Langue de Barbarie would be under water within 10 years. I looked at the big black bird; it looked back at me. I wondered when it, too, would be forced to leave an area growing smaller with each storm.

Colorful Woman

Avenue Dodds

As Ismael walked south down the street, Sylvie walked with him while François, Lomax, and Madeline followed. I stopped for a moment to look at my iPhone. I wondered if my boss in Washington, D.C., had provided any guidance for a new project regarding the Sahel. When I didn’t see any messages from anyone in the U.S., I put away my phone and rushed to catch up with the others, looking to the right toward the ocean, now less than 200 yards away. Although it was almost 3:00pm, the rays of the sun beat down hard, and I felt a wind coming off the ocean, picking up strength, providing some relief.

My companions had passed through the intersection of Avenue Dodds and a smaller street, Rue Camille Guy, as I re-joined them on the west side of Avenue Dodds.

Sylvie approached a small girl and much smaller boy who were digging in the sand with a blue plastic shovel in front of an open doorway.

“Give some candy to these two,” Sylvie said to Ismael in French.

Ismael moved forward and reached into his plastic bag. When the girl, who was about 4 years old, and the boy, about 3 years old, looked up, Ismael gave each child a large piece of chocolate in a wrapper. The candy looked like Snickers bars. Sylvie squatted down next to the boy and girl, smiling and talking in French for a few moments before standing up again. Madeline approached and put her arm around Sylvie, and the two spoke for a moment.

I stopped on one side of the doorway of the apartment building, which was painted a light shade of blue and which extended up three levels. Each of the second and third stories featured a narrow balcony with a dusty view of Avenue Dodds.

When I shifted my gaze back to Sylvie, she appeared emotional. I knew that she was from Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, and still had family members in Africa. I also knew she had started her studies at one of Yaoundé’s most prestigious schools, Université de Dschang. I wondered what kind of influence her African relatives had on her, whether she kept in touch with them or had seen them recently. I also considered her relationship with her brother, Yves, who lived in Paris and played tennis professionally. I had read about him in the sporting news. I understood Yves and Sylvie had been close before moving to France from Cameroon.

The day before, Friday, Madeline had told me that Sylvie’s younger brother, the tennis player, had not been the first in her family to be recruited by the French Tennis Association and its coaches. Sylvie had been their initial target. When she moved to Paris, her younger brother had accompanied her, but Sylvie, who had been studying biology in Yaoundé, gave up tennis in Paris and began studying biology and anatomy full time and later enrolled in medical school. Sylvie was 6 feet, 2 inches tall, but her brother later grew to 6 feet, 5 inches tall. He became the star athlete, not her.

Lomax and François took photos of the two children. Lomax asked Sylvie to pose with the children digging in the sand.

Suddenly, a woman carrying a child in her arms passed through the doorway, exiting the apartment building and stopping in front of us. I could detect vague shapes in the dimly lit room behind the woman. To the left of the doorway, attached to a one-story structure occupying an adjacent lot, was a long, wooden bench on which four men sat. All of them were staring at us. They appeared to be disapproving, and distracted me.

Sylvie reached into the plastic bag in Ismael’s hand, grasped a caramel wrapped in red wax paper, and placed the candy in the small hand of the child, who was a girl of 5 or 6 years with sunken features around her eyes and a pained expression in the lines on her face. It was clear the girl was ill.

“She is sick, isn’t she?” Sylvie asked the woman in French as the small girl put the caramel in her mouth. Sylvie turned to Ismael and in French said, “Ask her in Wolof if the girl is sick.” Another figure, at that moment, emerged from the doorway and made a straight line toward Sylvie. It was a tall girl, an adolescent, who was 12 or 13 years old and whose hair was arranged in corn rows. She held out her hand. She appeared to be another daughter of the woman.

Girl with Braids

Madeline removed a lollipop from Ismael’s bag and put it in the palm of the tall girl’s hand.

Lomax inched forward and took a photo of the mother with her daughter and then one of the tall girl. I knew Lomax wanted images of the woman and all of her children. At the same time, François started speaking in French to one of the men sitting on the bench, although it wasn’t clear how well the man understood what François was saying. The man didn’t reply, and his three companions wore blank expressions on their faces.

The mother holding the small girl, still smiling, apparently was happy with the attentions of Sylvie, and nodded her head at Sylvie but did not speak to her.

“What are her symptoms?” Sylvie asked in French, cupping the small girl’s face in her left hand and examining the girl’s eyes. The mother replied, addressing Ismael and speaking in Wolof.

“The girl has a fever and diarrhea,” Ismael translated from Wolof to French for Sylvie. “Also the girl is not eating, and she is weak.” He paused. “The mother worries about her daughter, but she doesn’t have money to take her to the hospital on the mainland or even to a local clinic. The mother doesn’t know what to do.”

“How long has your daughter been sick?” asked Sylvie in French, shifting her gaze from the girl to the woman, who evidently understood French but did not speak it. Madeline stroked the girl’s cheek, and then put her hand on the girl’s forehead.

The woman spoke in Wolof to Ismael, who replied in French to Sylvie.

“Three days,” Ismael said.

“Mon Deu,” Sylvie said. “The little girl is much too hot,” Sylvie continued, now speaking in English. “She has a high temperature.” Sylvie paused. “I think she has E. coli.” Looking at the mother, Sylvie added in French, “I am a doctor.” Ismael translated again, even if it wasn’t necessary, and added several sentences of his own.

Sylvie reached into the bag hanging from her shoulder and removed a plastic container with pills. “She needs to be treated immediately,” Sylvie continued in English, giving the container to the woman. “Here is an anti-biotic medicine which will help your daughter,” Sylvie said, switching to French while glancing from the woman to Ismael. “But you need to take the child to see a doctor,” Sylvie added in French, looking at the woman and then nodding at Ismael to prompt him to translate her words into Wolof. Ismael repeated Sylvie’s words in Wolof. “Here is some money,” Sylvie continued in French, pressing some bills into the woman’s hand. “Can you go today? This afternoon?”

Children Eating Candy

Sylvie, after she had finished talking with the mother, expressed optimism to Madeline that the girl would recover, but, as Sylvie walked with Lomax and me behind Ismael in a southerly direction on the 3rd block of Avenue Dodds, she promised she would check on the girl the following week. We would return from Podor in 5 days. Sylvie said she’d read about the incidents of E. coli in West Africa in a medical journal before traveling to Mali and Senegal, and already doctors in Dakar and St. Louis were fighting epidemics.

I removed the water bottle from my pack and drank while I surveyed the scene along Avenue Dodds. It was at once interesting and disturbing. On both sides of the street, extending north and south as far as the eye could see, were lines of towering wooden poles, probably supporting exposed electrical wires connected to other poles which passed by tightly packed, crumbling clusters of buildings, some with one or two levels and others with as many as three levels. Among the clusters of partially destroyed or half-constructed structures baking in the heat were heaps of garbage strewn across sand-covered and very small front yards and other larger or full-sized lots.

On one side of me, Madeline and Sylvie were talking in French between themselves as they walked side by side. On the other side, François was posing questions to Ismael about the effects of rising seawater on La Langue de Barbarie.

Lomax was nowhere to be seen.

François commented loudly. “It’s just one long, narrow bank of sand,” he continued. “In certain places, it’s no more than 300 feet from one side to the other.” He paused. “How can people continue to live here?”

Ismael was blunt. “They can’t,” he replied. “Every day more sand disappears from under their feet.” He paused. “The rapid erosion of the peninsula started about 5 years ago, when we had a big storm. The heavy rain fall lasted for days and caused flooding and changed the land, making it smaller and smaller.” He stuttered and looked westward. “At least one community already is gone for good.”

Ismael referred to a community I had heard about called Doune Baba Dieye located south of Guet N’Dar near the mouth of the river. When flood waters forced the people from their homes, the deluge never receded, leaving behind a lagoon where none existed before. The result was that, after the residents of Doune Baba Dieye fled to higher ground on the eastern side of the Senegal River, they couldn’t return. They had to move into tents at a migrant camp called Khar Yalla 5 miles inland, not far from the small airport serving St. Louis.

Abruptly, Ismael came to a halt. François stopped next to him, and Madeline and Sylvie crossed over from the opposite side of Avenue Dodds. I arrived a few moments later. We faced toward the ocean, standing in the middle of an intersection, where a narrow, sand-covered street, not much bigger than a path, cut through Avenue Dodds and extended to the beach. I didn’t know where we were, since I hadn’t studied my map for this part of La Langue de Barbarie in my hotel room.

Then, in the background, a thin blue line—it was the Atlantic—became visible. But the view of the ocean was then interrupted. A large building, about four stories high with two towers or minarets reaching even higher toward the sky, sat on the edge of the beach. Not only was the building recently and completely constructed; also, it appeared to be well, even meticulously, maintained.

Lomax materialized once again.

“Ismael,” Lomax called out from a distance of 20 feet, removing an oversized black baseball cap with an image of a raven on it and exposing his blond hair. “That building is a mosque, isn’t it?” He paused, running his hand across his forehead. “I want us to walk over to it so I can photograph it up close and talk with people standing around the entrance.”

“Yes,” Ismael replied, looking at Lomax but not hiding his irritation. “That was my idea.” He pointed toward the structure, painted white but also featuring a green trim on the wooden slats covering the windows of its main body and covering the windows on its towers. “The building is sacred,” Ismael shouted out. “It’s the mosque for Guet N’Dar.” He paused. “I’ll show it to you,” he said in a reduced voice. I detected an almost reverential quality in his voice.

Exposed Electrical Wires

Mosque

It was obvious Ismael was Muslim, although the idea that he was religious seemed preposterous given his habit of drinking beer continuously.

Ismael started toward Lomax, but Lomax, replacing the baseball cap, turned around and proceeded down the sandy path toward the mosque. Ismael was upset.

François quickly followed Lomax, giving the impression he didn’t want to waste time taking photos of the mosque from a distance. Sylvie and Madeline also started toward the people standing in front of the building.

As I shifted my gaze from Ismael, I stared at a clothes line stretching from the side of a house to a metal pole with many articles of clothing and bed linens on it flopping in the wind. I also saw the faded words, Rue Justin Devest, on a small street sign partially dislodged from its bolts on a one-story building. The street sign hung upside down.

After a few moments, Ismael followed the two Parisian women and François and Lomax. I stayed behind at the intersection for a couple of moments, not moving until I saw Ismael catch up with Lomax.

Once in motion, I moved swiftly, seeing the beach and the waves of the Atlantic clearly as I drew closer.

Reaching the end of Rue Justin Devest, I looked across the yellow sand of the sunlit beach. I saw a gurgling foam on a surf which didn’t cease. I looked into an unmoving blue void of ocean on the horizon. I felt a mild wind blowing against me, free of any man-made or natural obstructions, causing me to shiver in spite of the sun’s rays. Finally, I heard the sound of voices on a sunny afternoon, and I thought about the fishermen of La Langue de Barbarie who suffered the full force of powerful winds in the middle of the sea as their boats capsized in towering waves and their bodies sank in the depths. They had no hopes of escaping.

But I sensed a more immediate presence. Directly in front of the mosque, I saw people passing through the main doors on the south side of the building, facing Rue Justin Devest. I knew about Islam’s daily five calls to prayer and assumed the fourth one of the day, called salat al-‘asr, held during the middle of the afternoon, was about to start. I had not heard the call itself from loudspeakers on the minarets. But I knew that not all mosques broadcasted their calls to prayer into nearby neighborhoods.

“My father and my older brother pray here,” a teen-age girl was saying in French to Madeline. “They can’t come every day when they are at sea, but my father, who is sick right now, usually can make it to the fourth call.”

The girl looked like she was 16 years old. Next to her was another teen-age girl, possibly a year younger. It was obvious the two were sisters. They looked alike, and in addition, the younger girl held the hand of a small boy, possibly 4 years old, who closely resembled his sisters. He was a much younger brother.

“Do you live close to the mosque?” Sylvie asked in French, looking at the younger girl.

“Yes, not far from here,” the girl replied, proceeding to launch into an elaborate description in French of the route from her family’s home to the mosque. She lifted the small boy into a position on her hip.

The two teen-age girls and their younger brother stood in front of a motorcycle which was propped up against a short wall directly across Rue Justin Devest.

“The motorcycle belongs to my older brother,” the youngest girl said, noticing Sylvie looking at the bike. “He is proud of it,” she added, “and sometimes takes one of us on the back with him.”

Madeline and Sylvie stood at the end of the sandy street, just off the sunlit beach stretching out 100 yards behind them.

Not far away, Lomax and François huddled together peering into the small LCD at the back of Lomax’ big camera, each of them eating a chocolate bar. Ismael stood behind them, also eating candy. Lomax had taken a series of images of the mosque and the people arriving for prayer.

“Hey, what are you doing? Don’t eat that candy,” Madeline shouted upon noticing Lomax, Ismael, and François holding chocolate bars. A frown appeared on her face. “Bring the rest of the candy over here,” she instructed. When she turned around and spotted me, she shouted again, “You have to meet Awa, Khady, and Moussa.” She shouted again, “Bring the bag to Sylvie and me. We’ll look after it.”

I had noticed the girls and the little boy when they greeted Madeline and Sylvie a few minutes before. Now, as I walked toward them, I thought they’d be good subjects for Lomax and his photography.

Sisters with Little Brother

The two sisters, Awa and Khady, spoke skillfully in French. The girls seemed intelligent, but also they had gone to school for a number of years. Their teachers not only taught a curriculum exclusively in French. They also drilled the students in French grammar. The words which Awa and Khady used and the manner in which they pronounced words were sophisticated, according to Sylvie.

The little boy, Moussa, initially focused on Madeline and Sylvie. Since he had two older sisters, he was accustomed to seeing females telling males what to do. Sylvie, especially, who was tall and assertive, commanded his attention.

Within a few minutes, though, Moussa had shifted his attention to Lomax and François. He was fascinated by the candy they were eating.

When Lomax started taking photos of Awa and Khady, they started laughing. They placed Moussa in different positions in front of them, tickling him to make him laugh. After Madeline took the bag of candy out of Ismael’s hands, she held it open for the siblings. Moussa looked at the plastic sack and plunged a hand down into it.

“Your French is excellent,” Sylvie commented to Awa, 16, the older of the two sisters, who watched Moussa grab a caramel wrapped in red wax paper and, in his excitement, fall over in the sand. “Not many people in Africa who go to school ever learn French as well as you have,” Sylvie added, glancing at the boy, who jumped up from the sand. He couldn’t remove the red wax paper around the caramel.

“Do you still go to school?” Sylvie asked Awa.

Awa shook her head.

“No,” Awa said, “I quit school last year to help my mother clean fish.”

Watching Moussa as he struggled to release the candy from the wax paper, Madeline exclaimed in French, “Oh, how dirty your hands are,” and squatted next to the boy. Moussa, thinking Madeline wanted to take away his candy, jerked the caramel free of the wax paper and shoved it in his mouth.

Madeline, examining Moussa’s hands, removed a cleansing wipe from her bag and rubbed his hands with it. When Madeline finished, Sylvie took over and cleaned his hands a second time more thoroughly.

Moussa squirmed. Sylvie was too strong.

“There,” Sylvie said, “Isn’t that better?”

“No,” Moussa said. Both Awa and Khady laughed and mimicked Moussa. “You are not my mother,” he said in French to Sylvie.

“Little boys like you,” Sylvie said, “are always dirty. You always need a bath.”

Awa and Khady couldn’t stop giggling. They locked their hands and danced in a circle as the tide crept up the beach, drawing ever closer.

**